The Death of "Saving Up": From Extreme Frugality to Soft Saving

The old way of saving—being extremely frugal—doesn’t really work in today’s world. Now, people are turning to ‘soft saving,’ which translates to saving when you can but also allowing yourself to enjoy life in the moment.

“Real generosity toward the future lies in giving all to the present.” —Albert Camus

Yes, we now begin money articles with Camus quotes. I hope I haven't lost you already! But it's a great quote that helps frames a question many of us face: how do you enjoy life now while also planning for what’s ahead?

For a long time, being responsible meant saving up and putting off things you wanted now to feel secure later. The FIRE movement—Financial Independence, Retire Early—became popular in the 2010s as an extreme version of this idea. But things have shifted in recent years. Now, the balance between present enjoyment and future security is evolving. In this article, we’ll explore what FIRE is, why it’s lost some steam, what’s taking its place, and why more people are focusing on living in the moment while still thinking about the future.

1. A Short History of FIRE

FIRE stands for Financial Independence, Retire Early. It began with just a few blogs in the 2010s that celebrated strict saving. Jacob Lund Fisker’s book Early Retirement Extreme and the blog Mr. Money Mustache became well-known for encouraging people to live well below their means, save more than half of each paycheck, invest the rest, and leave the nine-to-five life much earlier than usual.

One of its key principles was to determine your Financial Independence Number. The simplest version was to determine your annual expenses and then multiply by 25.

At its heart, FIRE wasn’t just about retiring. It was about choosing a different path: working hard now so you could step away from work for good later.

For a while, FIRE seemed like the solution. But then rents in big cities doubled, wages stopped growing, and the cost of assets rose faster than incomes. Stories about early retirees living off index funds in cheap towns no longer made sense to younger people struggling with high rent and grocery bills.

A Fortune profile of a twenty-something surviving on 65-cent breakfasts to reach financial independence by forty landed less as inspiration and more as absurdist comedy (Fortune).

Even FIRE icon Mr. Money Mustache later wrote that many readers had missed the point, confusing freedom with extreme frugality (Mr. Money Mustache). FIRE, he said, was never meant to be about deprivation; it was about using money to build a better life.

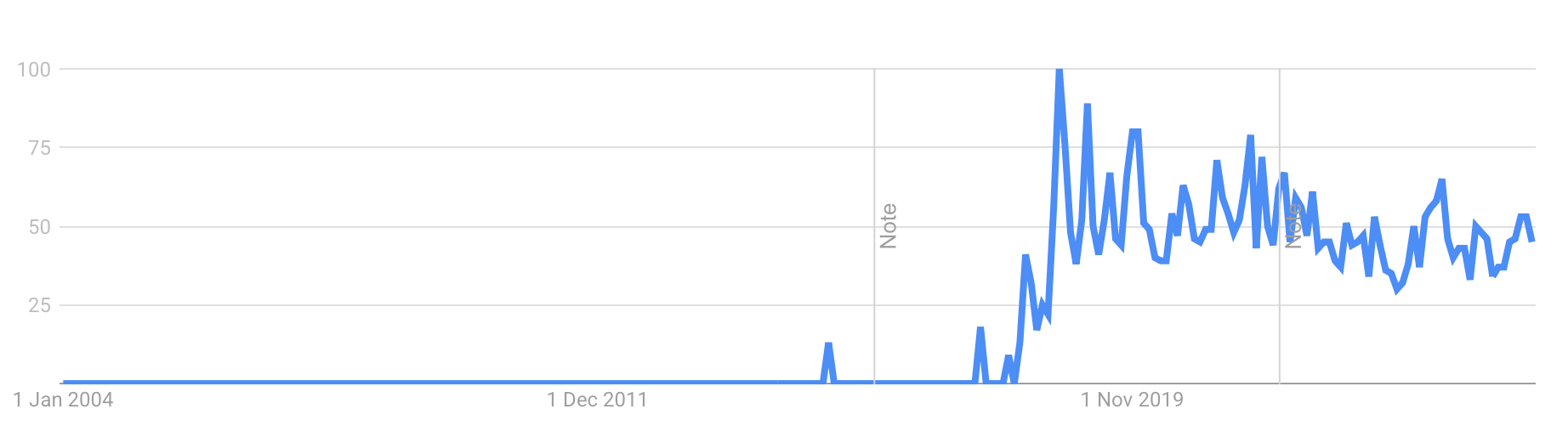

Meanwhile, Google Trends data for “FIRE financial independence retire early” shows that interest peaked around 2020 and has since started to decline.

Still, it left a cultural footprint. FIRE made optimization feel normal. It introduced the idea that your entire financial life could be designed and automated. That mindset remains, but it’s softened. What used to be a lifelong project has become a series of smaller experiments.

2. The Rise and Retreat of the Early Retirees

When FIRE peaked around 2020, it gave savings a sense of purpose. Blogs, YouTube channels, and Reddit threads turned thrift into a kind of performance art. But like most internet subcultures, it began to collapse under its own weight.

People discovered that freedom wasn’t a one-time transaction. It wasn’t something you unlocked by denying yourself enough. It was a moving target, dependent on health, work, and circumstance. The fantasy of total independence began to give way to smaller, more manageable definitions of control.

A New York Times Magazine piece on early retirement noted that “But I always end up coming to the same conclusion: There’s no point in making so much money if you’re not going to be happy. I’d rather be free.” People want autonomy more than escape.

3. Saving in Seasons: No-Buy, Soft Saving

In place of lifelong thrift, Gen Z is experimenting with short-term, high-intent saving.

“No-buy months” originated as TikTok challenges and have evolved into seasonal rituals. Reddit communities like r/NoBuy and r/LowBuy fill with posts charting the small satisfactions of abstaining.

These saving strategies borrow from minimalism, therapy culture, and gamified self-improvement. Saving becomes a period of focus, not a lifelong posture.

It’s the same cultural logic that turned “dry January” or “screen-free Sundays” into modern rituals.

New vocabulary has also emerged: “soft saving.” It describes a generation choosing flexibility over extreme thrift. The goal isn’t to retire early; it’s to keep options open. This quote from a Guardian article perfectly encapsulates the movement:

“I don’t want to miss out on opportunities when I am young, but I also don’t want to go into debt.”

4. What Comes After Saving Up

If saving no longer commands the gravity it once did, what replaces it? The answer lies in new definitions of financial wellness.

Today, financial wellness might mean going through cycles: saving for a while, then taking a break. People are planning with more flexibility instead of aiming for strict goals. They are accepting that the future is uncertain and making room for some spontaneity, even when there are limits.

The death of “saving up” doesn’t mean the end of planning. It means the end of treating life as something to postpone.